The two models we will discuss, the linear model and the transactional model, include the following parts: participants, messages, encoding, decoding, and channels (ISU, 2016). In the models, the participants are the senders and/or receivers of messages in a communication encounter. The message is the verbal or nonverbal content being conveyed from sender to receiver (ISU, 2016). For example, when you say “hello” to your friend, you are sending a message of greeting that will be received by your friend.

The basic components listed below apply to both models:

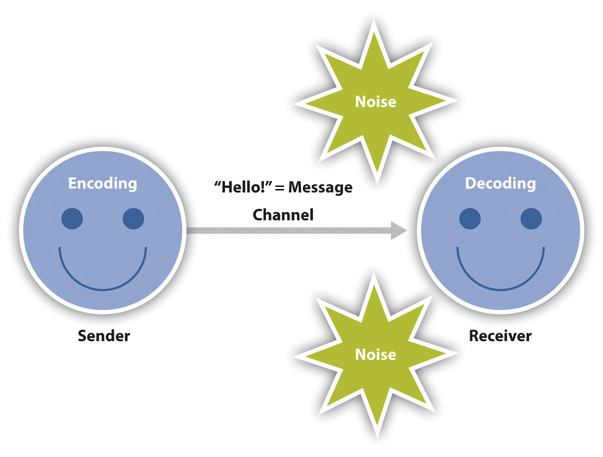

The linear model (originally called the mathematical model of communication) serves as a basic model of communication and was developed by Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver in 1949. This model suggests that communication moves only in one direction from one source to another (ISU, 2016). The sender encodes a message, then uses a certain channel (verbal or nonverbal communication) to send it to a receiver who decodes (interprets) the message. You also act as the receiver when you watch a video or receive a message from another source. Noise is anything that interferes with, or changes, the original encoded message (ISU, 2016). Image 1.4 is a basic illustration of the linear model, and the video below provides an overview of this model of communication.

(Communication Studies, 2020)

A major criticism of the linear model of communication is that it suggests communication only occurs in one direction (ISU, 2016). This model also does not show how context, or our personal experiences, impact communication. Television serves as a good example of the linear model. Have you ever talked back to your television while you were watching it? Maybe you were watching a sporting event or a dramatic show and you talked at the people on the television. Did they respond to you? We’re sure they did not. Television works in one direction. No matter how much you talk to the television it will not respond to you. Now apply this idea to the communication in your relationships. It seems ridiculous to think that this is how we would communicate with each other on a regular basis. This example shows the limits of the linear model for understanding communication, particularly human-to-human communication (ISU, 2016).

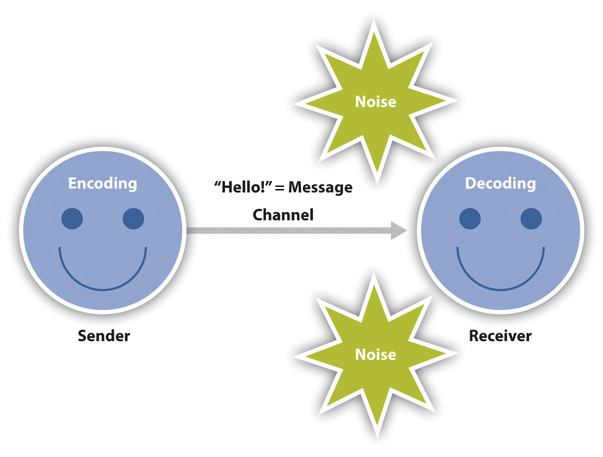

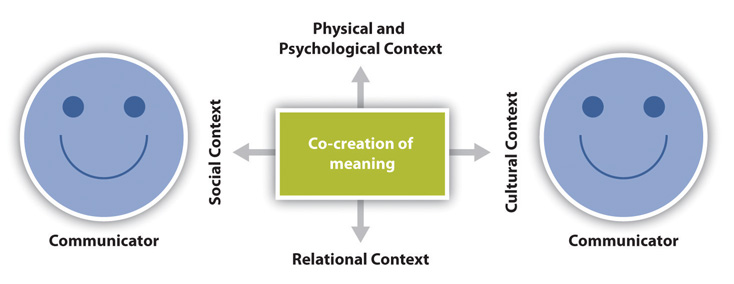

The transactional model, which was adapted by Dean Barnlund in 1970, demonstrates that communication participants act as senders and receivers simultaneously, creating reality through their interactions (ISU, 2016). Communication is not a simple one-way transmission of a message—the personal filters and experiences of the participants impact each communication exchange. The transactional model demonstrates that we are simultaneously senders and receivers and that noise and personal filters always influence the outcomes of every communication exchange (ISU, 2016). This more complex model of commination is shown in Image 1.5.

This model also suggests that meaning is co-constructed between all parties involved in any given communication interaction. This notion of co-constructed meaning is drawn from the relational, social, and cultural contexts that make up our communication environments. Personal and professional relationships, for example, have a history of prior interaction that informs present and future interactions (ISU, 2016). Social norms, or rules for behaviour and interaction, greatly influence how we relate to one another. For example, if your instructor taught the class while sitting down rather than standing up, you and your colleagues would feel awkward because that is not an expected norm for behaviour in a classroom setting. How we negotiate cultural values, beliefs, attitudes, and traditions also impacts our communication interactions. Theses concepts are elaborated more below.

(Instructional Design Team – Seattle Central College, 2018)

The contexts below are all factors that affect communication and must be considered in any communication exchange:

The physical context includes the environmental factors in a communication encounter. The size, layout, temperature, and lighting of a space influence our communication. Imagine the different physical contexts in which job interviews take place and how that might affect your communication. I have had job interviews on a sofa in a comfortable office, sitting around a large conference table, and even once in an auditorium where I was positioned on the stage facing about 20 potential colleagues seated in the audience. I’ve also been walked around campus in freezing temperatures to interview with various people. Although I was a little chilly when I got to each separate interview, it wasn’t too difficult to warm up and go on with the interview. During a job interview in Puerto Rico, however, walking around outside wearing a suit in very hot temperatures created a sweating situation that wasn’t pleasant to try to communicate through. Whether it’s the size of the room, the temperature, or other environmental factors, it’s important to consider the role that physical context plays in our communication.

The psychological context includes the mental and emotional factors in a communication encounter. Stress, anxiety, and emotions are just some examples of psychological influences that can affect our communication. I recently found out some troubling news a few hours before a big public presentation. It was challenging to try to communicate because the psychological noise triggered by the stressful news kept intruding into my other thoughts. Seemingly positive psychological states, like experiencing the emotion of love, can also affect communication. During the initial stages of a romantic relationship, individuals may be so “lovestruck” that they don’t see incompatible personality traits or don’t negatively evaluate behaviours they might otherwise find off-putting.

Social context refers to the stated rules or unstated norms that guide communication. As we are socialized into our various communities, we learn rules and implicitly pick up on norms for communicating. Some common rules that influence social contexts include not lying to people, not interrupting people, greeting people when they greet you, thanking people when they pay you a compliment, and so on. Parents and teachers often explicitly convey these rules to their children or students.

Norms are social conventions that we pick up on through observation, practice, and trial and error. We may not even know we are breaking a social norm until we notice people looking at us strangely or someone corrects or teases us. For example, as a new employee you may over- or underdress for the company’s holiday party because you don’t know the norm for formality. Although there probably isn’t a stated rule about how to dress at the holiday party, you will notice your error without someone having to point it out, and you will likely not deviate from the norm again in order to save yourself from any potential embarrassment. Even though breaking a social norm doesn’t result in the formal punishment that might be a consequence of breaking a social rule, the awkwardness we feel when we violate social norms is usually enough to teach us that these norms are powerful even though they aren’t as explicit as rules. Norms even have the power to override social rules in some situations. To go back to the examples of common social rules mentioned before, we may break the rule about not lying if the lie is meant to save someone from feeling hurt. We often interrupt close friends when we’re having an exciting conversation, but we wouldn’t be as likely to interrupt a professor while they are lecturing. Since norms and rules vary among people and cultures, relational and cultural contexts are also included in the transactional model to help us understand the multiple contexts that influence our communication.

The relational context includes the previous interpersonal history and type of relationship we have with a person. We will communicate differently with someone we just met versus someone we’ve known for a very long time. Communication will also vary depending on the type of relationship we have with someone. For example, there are certain communication rules and norms that apply to a supervisor–supervisee relationship that don’t apply to a brother–sister relationship and vice versa. Just as social norms and relational history influence how we communicate, so does culture.

Cultural context includes various aspects of identities such as race, gender, nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, and ability. It is important for us to understand that whether we are aware of it or not, we all have multiple cultural identities that influence our communication. Some people, especially those with identities that have been historically marginalized, are regularly aware of how their cultural identities influence their communication and influence how others communicate with them. Conversely, people with identities that are dominant or in the majority may rarely, if ever, think about the role their cultural identities play in their communication.

Although some of these models are overly simplistic representations of communication, they illustrate some of the complexities of defining and studying communication. Hopefully, you recognize that studying communication is simultaneously detail oriented (looking at small parts of human communication) and far reaching (examining a broad range of communication exchanges). Knowledge of these models, their components, and how they apply in various contexts can show us how complex communication is. Because of this, it is also not surprising that often there may be communication challenges, but knowing why they occur—possibly owing to some of the factors discussed above—can help to avoid, or at least overcome, these challenges.

Forms of communication vary in terms of participants, channels used, and contexts. The five main forms of communication are intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, public, and mass communication.

Intrapersonal communication is communication with oneself using internal vocalization or reflective thinking, as shown in Image 1.6. Like other forms of communication, intrapersonal communication is triggered by an internal or external stimulus. For example, the internal stimulus of hunger may prompt us to communicate with ourself about what we want to eat, or we may react intrapersonally to an event we witness. Unlike other forms of communication, intrapersonal communication takes place only inside our head. The other forms of communication must be perceived by someone else to count as communication. So what is the point of intrapersonal communication if no one else is aware of it?

Intrapersonal communication serves several social functions. For example, a person may use self-talk to calm down in a stressful situation, or a shy person may remind themself to smile during a social event. Intrapersonal communication also helps build and maintain our self-concept. We form an understanding of who we are based on how other people communicate with us and how we process that communication intrapersonally. The shy person in the earlier example probably internalized shyness as part of their self-concept because other people associated that individual’s communication behaviours with shyness and may have even labelled that person “shy” before they had a firm grasp on what that meant. We also use intrapersonal communication, or “self-talk,” to let off steam, process emotions, think through something, or rehearse what we plan to say or do in the future. As with the other forms of communication, competent intrapersonal communication helps facilitate social interaction and can enhance our well-being.

Sometimes we communicate intrapersonally for the fun of it. I’m sure we have all had the experience of laughing aloud because we thought of something funny. We also communicate intrapersonally to pass time. There is likely a lot of intrapersonal communication going on in waiting rooms all over the world right now. We can, however, engage in more intentional intrapersonal communication. In fact, deliberate self-reflection can help us become more competent communicators as we become more mindful of our own behaviours. For example, your internal voice may praise or scold you based on a thought or action.

Of all the forms of communication, intrapersonal communication has received the least amount of formal study. It is rare to find courses devoted to the topic, and it is generally separated from the remaining four types of communication. The main distinction is that intrapersonal communication is not created with the intention that another person will perceive it. In all the other forms, the fact that the communicator anticipates consumption of their message is very important.

Interpersonal communication is communication between people whose lives mutually influence one another. This type of communication builds, maintains, and ends our relationships, and we spend more time engaged in interpersonal communication than the other forms of communication. Interpersonal communication occurs in various contexts and is addressed in subfields of study within communication studies, such as intercultural communication, organizational communication, health communication, and computer-mediated communication. After all, interpersonal relationships exist in all those contexts.

Interpersonal communication can be planned or unplanned, but because it is interactive, it is usually more structured and influenced by social expectations than intrapersonal communication. Interpersonal communication is also more goal-oriented than intrapersonal communication and fulfills instrumental and relational needs. In terms of instrumental needs, the goal may be as minor as greeting someone to fulfill a morning ritual or as major as conveying your desire to be in a committed relationship with someone. Interpersonal communication meets relational needs by communicating the uniqueness of a specific relationship. Couples, bosses and employees, and family members all have to engage in complex interpersonal communication, and it doesn’t always go well. In order to be a competent interpersonal communicator, you need conflict management skills and listening skills, among others, to maintain positive relationships.

Group communication is communication among three or more people interacting to achieve a shared goal. You have likely worked in groups in high school and college, and if you’re like most students, you didn’t enjoy it. Even though it can be frustrating, group work in an academic setting provides useful experience and preparation for group work in professional settings. Organizations have been moving towards more team-based work models, and whether we like it or not, groups are an integral part of people’s lives. Therefore, the study of group communication is valuable in many contexts.

Group communication is more intentional and formal than interpersonal communication. Unlike interpersonal relationships, which are voluntary, individuals in a group are often assigned to their position within the group. Additionally, group communication is often task focused, meaning that members of the group work together for an explicit purpose or goal that affects all the members of the group. Goal-oriented communication in interpersonal interactions usually relates to one person; for example, I might ask a friend to help me move this weekend. At the group level, goal-oriented communication usually focuses on a task assigned to the whole group; for example, a group of people may be tasked to figure out a plan for moving a business from one office to another.

You know from previous experience working in groups that having more communicators usually leads to more complicated interactions. Some of the challenges of group communication relate to task-oriented interactions, such as deciding who will complete each part of a larger project. But many challenges stem from interpersonal conflict or misunderstandings among group members. Because group members also communicate with and relate to each other interpersonally and may have preexisting relationships or develop them during the course of group interaction, elements of interpersonal communication occur within group communication, too.

Public communication is a sender-focused form of communication in which one person is typically responsible for conveying information to an audience. Public speaking, as shown in Image 1.7, is something that many people fear, or at least don’t enjoy. But just like group communication, public speaking is an important part of our academic, professional, and civic lives. When compared to interpersonal and group communication, public communication is the most consistently intentional, formal, and goal-oriented form of communication we have discussed so far.

Public communication, at least in Western societies, is also more sender focused than interpersonal or group communication. It is precisely this formality and focus on the sender that makes both new and experienced public speakers anxious at the thought of facing an audience. One way to begin to manage anxiety about public speaking is to try to see connections between public speaking and other forms of communication with which we are more familiar and comfortable. Despite being formal, public speaking is very similar to the conversations that we have in our daily interactions. For example, although public speakers don’t necessarily develop individual relationships with audience members, they still have the benefit of being face-to-face with them so they can receive verbal and nonverbal feedback.

Public communication becomes mass communication when it is transmitted to many people through print or electronic media. Print media such as newspapers and magazines continue to be an important channel for mass communication, though they have suffered much in the past decade due in part to the rise of electronic media. Television, as shown in Image 1.8, websites, blogs, and social media are mass communication channels that you probably engage with regularly. Radio, podcasts, and books are other examples of mass media. The technology required to send mass communication messages distinguishes it from the other forms of communication. A certain amount of intentionality goes into transmitting a mass communication message because it usually requires one or more extra steps to convey the message. This may require pressing “Enter” to send a Facebook message or involve an entire crew of camera people, sound engineers, and production assistants to produce a television show. Even though the messages must be intentionally transmitted through technology, the intentionality and goals of the person actually creating the message, such as the writer, television host, or talk show guest, vary greatly.

Mass communication differs from other forms of communication in terms of the personal connection between participants. Even though creating the illusion of a personal connection is often a goal of those who create mass communication messages, the relational aspect of interpersonal and group communication isn’t inherent in this form of communication. Unlike interpersonal, group, and public communication, there is no immediate verbal and nonverbal feedback loop in mass communication. Of course, you could write a letter to the editor of a newspaper or send an email to a television or radio broadcaster in response to a story, but the immediate feedback available in face-to-face interactions is not present. With new media technologies such as Twitter, blogs, and Facebook, feedback is becoming more immediate. Individuals can now tweet directly “at” (@) someone and use hashtags (#) to direct feedback to mass communication sources. Many radio and television hosts and news organizations specifically invite feedback from viewers/listeners via social media and may even share the feedback with the audience.

The technology to mass produce and distribute communication messages brings with it the power for one voice or a series of voices to reach and affect many people. This power makes mass communication different from other levels of communication. Although there is potential for unethical communication at all the other levels, the potential consequences of unethical mass communication are important to consider. Communication scholars who focus on mass communication and media often take a critical approach in order to examine how media shapes our culture and who is included and excluded in various mediated messages.

Relating Theory to Real Life

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been reproduced or adapted from the following resource:

University of Minnesota. (2016). Communication in the real world: An introduction to communication studies. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, except where otherwise noted.

References

Barnlund, D. (1970). A transactional model of communication. Harper & Row.

Communication Studies. (2020, 14 November. Linear model of communication [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=27V1bg0jqXc

Department of Communication, Indiana State University (ISU). (2016). Introduction to public communication. Indiana State University. http://kell.indstate.edu/public-comm-intro/, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Instructional Design Team – Seattle Central College. (2018, 15 November). Transactional model [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nHDfF395BRk

Shannon, C., and Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press. https://raley.english.ucsb.edu/wp-content/Engl800/Shannon-Weaver.pdf

Image Credits (images are listed in order of appearance)