Many JVs and partnerships are built on co-creating and jointly commercializing IP. Our analysis of IP provisions across 38 JVs and non-equity partnerships offers guidance for developing an IP governance approach.

Tracy Branding Pyle

DECEMBER 2022 — While M&A markets are cooling, there has been no slowing of joint ventures and other types of partnerships. In fact, the volume of material new joint ventures and partnerships had a record first half in 2022 – up 39% from the same period in 2021 – and was almost 200% higher in the last 24 months than historic norms. Honda and Sony announced a joint venture to create a new electric vehicle brand and mobility service. PepsiCo and Beyond Meat formed a joint venture to develop and market plant-based protein snacks and beverages. And firms like BP, Shell, Orsted, and Fortescue continued to invest heavily in partnerships across renewable energy – from solar, offshore and onshore wind and hydrogen to carbon capture and energy storage.

Many of these new-era JV s and partnerships are built on co-creating and jointly commercializing intellectual property. At the same time, trade tensions with China – in part tied to alleged theft of IP, often through joint ventures with U.S. and European companies – have come to infuse boardroom discussions. For the first time, the U.S. government used the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to block an IP partnership – the proposed robotics joint venture between the U.S. company Ekso Bionics and two Chinese counterparties that was to use technology licensed from the U.S. partner to develop, manufacture, and market robotic exoskeletons for medical and industrial use in China and other markets.

" * " indicates required fields

Given this backdrop, we wanted to understand how existing joint ventures and partnerships approach IP governance. To do this, we benchmarked IP provisions across 38 joint ventures and non-equity partnerships where technology was core to the deal’s purpose. For each deal, we reviewed IP-related terms in the JV Agreement, a license agreement providing parent technology to the partnership, or both the JV agreement and license agreement for the partnership. [1] All JV Agreements corresponded to equity joint ventures. Some of the license agreements were for equity joint ventures and others were for non-equity partnerships.

Below we summarize our findings.

Intellectual property plays a prominent role in joint ventures and partnerships. Parent companies may inject their IP into a venture or partnership to provide needed capabilities and market differentiation. The venture may produce new IP during its lifetime, often working formally and informally with parent company employees to do so. And when the venture terminates, partners must decide who owns and can use these different kinds of IP. Corporate Boards, leadership teams, and those negotiating and structuring new JV s and partnerships need to ensure that contractual terms are carefully selected to reflect the issues and risks at all venture stages.

The specific IP terms in agreements need to be tailored to the overall deal objectives, corporate form, ownership structure, partner profiles, and nature of IP contributed, among other factors. That said, we believe it is valuable to understand how agreements are actually structured to identify strengths, gaps, and creative terms. Our benchmarking looked into three categories of contractual terms: (1) IP ownership, specifically of background and foreground IP; (2) IP licensing restrictions, including exclusivity, sub-licensing, and other restrictions, or parent company contributed IP; and (3) IP governance, including responsibilities for enforcement, filing and maintenance, and notice requirements for suspected infringements of IP.

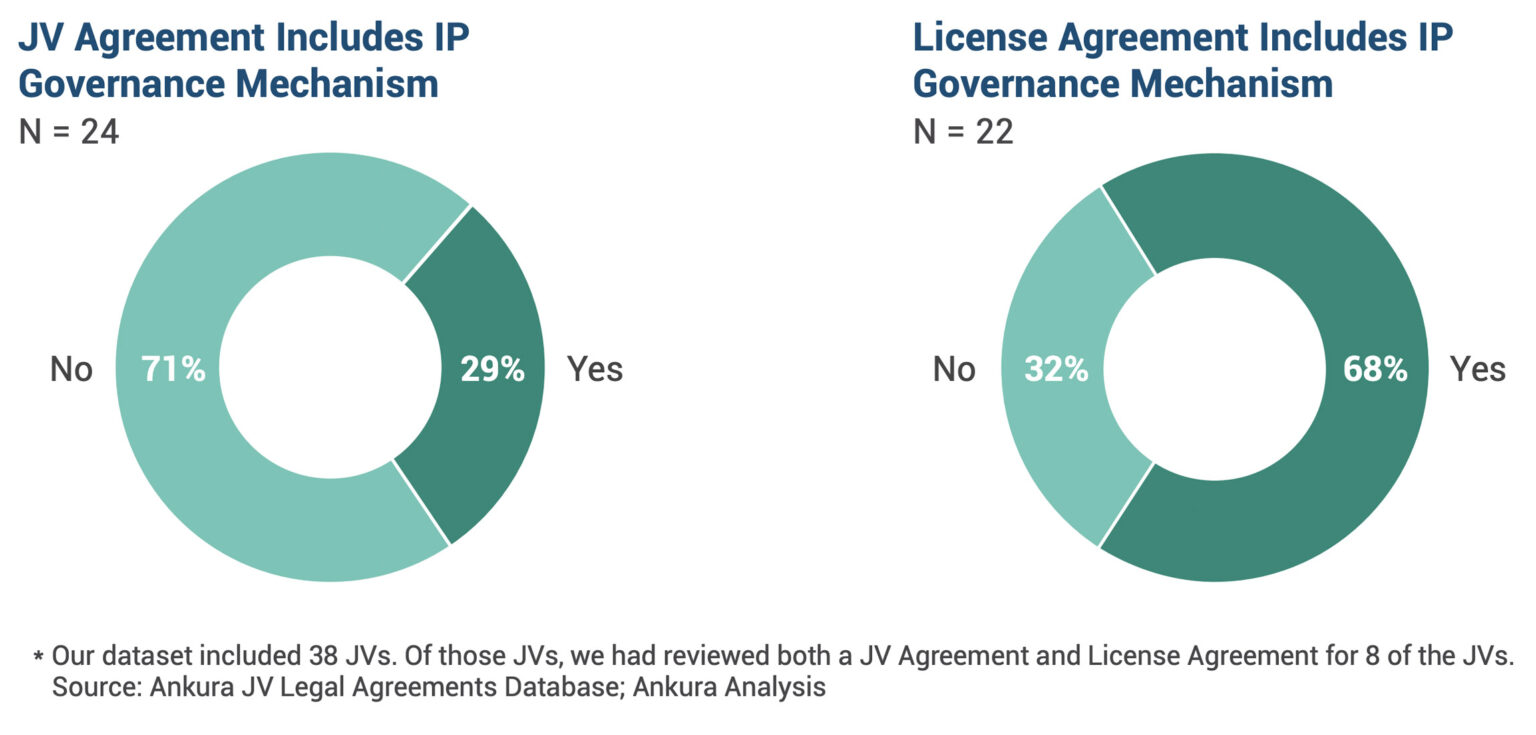

Our review revealed some interesting facts about approaches to IP ownership and licensing. But what we found most surprising was that few agreements made any explicit arrangements for how IP matters would be addressed during the life of the partnership. It’s generally understood that IP-related questions will arise during the life of a venture or collaboration, and these questions may not be able to be answered based solely on who owns the IP or has usage rights. But relatively few agreements provide detailed provisions for how to govern IP matters when they arise. Only 29% of the joint venture agreements we reviewed included at least one provision for governance of IP, while 68% of license agreements included such a provision (Exhibit 1).

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

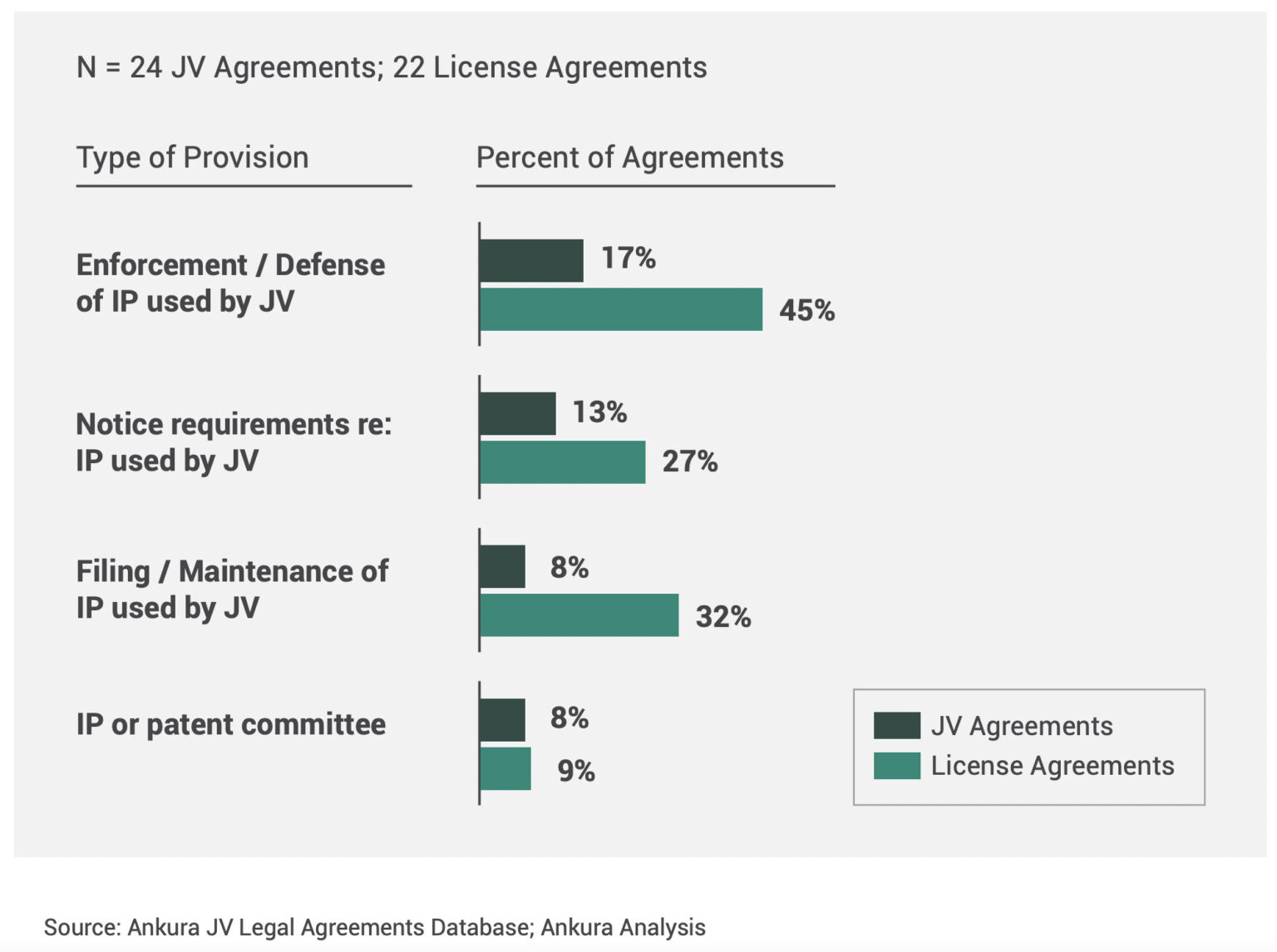

We looked at the prevalence of the four most common IP governance mechanisms seen in JV agreements and license agreements (Exhibit 2), as well as how these terms were actually structured.

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

The most common IP governance provision relates to who should enforce IP rights – either by filing against third parties viewed as infringing on the IP used by the partnership or by defending infringement actions brought against the owner of IP used by the partnership. 17% of JV Agreements and 45% of license agreements included these provisions. These clauses answer critical questions such as: Is the JV or a particular parent or multiple parents responsible for filing or defending infringement claims? Must partners coordinate their approach and share costs, particularly for IP that is jointly-owned or owned by the JV? Must all parents bring the suit against infringements, or can a parent prosecute alone?

There is no one answer to these questions. In most cases, IP owned by parents and licensed to a partnership is enforced by the owner-parent. Consider Force Dynamics, a JV between General Dynamics and Force Protection to sell, produce, and service mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicles, such as vehicles used to protect military troops against improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The license agreement between Force Dynamics and the JV grants the owner of any infringed IP the absolute discretion to determine whether or not to take legal or other action against any third party. Other ventures added parties to this framework. For example, a biopharmaceutical joint venture gives one parent the right to first bring suit against a third party for IP infringement, with the joint venture having the right, but not the obligation, to join in the proceedings. Or, in a partnership between Boehringer Ingelheim and Macrogenics to develop antibody-based therapies, the agreement establishes that if Boehringer Ingelheim declines to initiate a lawsuit against a third-party infringement on IP used or created by the partnership, then Macrogenics may be able to step in and do so.

When IP is jointly-owned, parties often have the option, but not the obligation, to participate in infringement suits. For instance, in commercial trucking venture NC2 between Navistar and Caterpillar, either partner can enforce JV-created IP that is jointly owned by the partners. If only one partner wishes to pursue the enforcement action, it can do so but indemnifies the other partner for such a suit. If both wish to pursue the enforcement action, they cooperate to do so and share costs.

But omissions on these questions can cause problems. Consider, for instance, the 2008 court case of Lucent Techs., Inc. v. Gateway, Inc. Lucent developed new technology with a German company, Fraunhofer, to be owned jointly by both companies. Later, Lucent patented another piece of technology and sued Gateway and Dell for patent infringement on that technology. In response, the court dismissed Lucent’s claim because part of that technology relied on work developed with Fraunhofer, so Lucent lacked standing to bring this claim – unless Fraunhofer joined the suit. Companies need to prepare for situations like this by coordinating the procedure for enforcing IP in their legal agreements. And, when IP is crucial to venture success and the partnership operates in a competitive industry, partners should consider building in a backup plan so that if the party charged with enforcement declines to enforce, others can step in and protect IP that is critical to the JV’s success.

The agreements should establish which party is responsible for filing and maintenance of IP. While this is only relevant for certain types of IP, like patents, over a quarter of license agreements explicitly defined who was responsible for such activities, while JV Agreements were lower at 13%. Like provisions related to enforcement, owners are typically required and/or have discretion to prosecute, file, renew, and maintain their own IP that is licensed to the JV.

Consider the partnership between U.S.-based Cord Blood America and AXM Pharma, a Chinese pharmaceutical company, to process and store umbilical cord blood in China. Under the terms of the deal, the parties signed a license and cooperation agreement, and Cord Blood took a minority equity investment in AXM. The agreement for the deal states that Cord Blood has the sole right, at its sole expense, to prepare, file, prosecute and maintain any patents, copyrights or trademarks relating to its intellectual property. In another agreement, if a partner intends to abandon (i.e., not renew) a patent used by the JV, it must notify the other partner in the JV at least 30 days before the due date for such renewal and the partner may elect to pay and take action to maintain the patent.

Ensuring that IP like critical patents is properly filed and renewed can make or break whether a partnership is successful. Thus, JV partners would be wise to not only designate who has the right to prosecute patents but also to have such party covenant that they will file and maintain IP or, alternatively, that if they elect not to file or maintain IP, they provide the JV or other partners the opportunity to do so on their behalf.

Another important IP governance provision involves notification obligations. Parents want to maintain the integrity of their IP, and this requires knowing whether third parties are infringing on their IP and whether a suit has been filed related to it. To address information asymmetries that may prevent the JV or partners from knowing if or when IP is at risk, those negotiating and structuring agreements should include notice provisions that parents and/or the JV must report (a) any suspected infringement of IP used by the JV and/or (b) any infringement suit filed based on IP used by the partnership. In NC2, the Navistar-Caterpillar commercial trucking manufacturing venture, the parents and the JV were obligated to promptly notify one another about any third-party infringement claims. Similarly, the license agreement for a pharmaceutical JV requires the notifying party to provide other parties with all available evidence regarding such known or suspected infringement or unauthorized use, in addition to the notification of third-party infringement. Including notice provisions in partnership legal agreements can help all parties stay on the same page, prevent disputes, and protect IP. Thus dealmakers should seriously consider including notice requirements related to IP.

A few of the joint ventures and partnerships in our dataset required the partners to have an intellectual property or patent committee that was charged with making or advising on IP-related decisions during the lifetime of the partnership. This type of committee is highly common in certain industries, such as in healthcare or pharmaceutical partnerships. In fact, most of the healthcare strategic partnerships we reviewed had a patent committee. In Pfizer-BioNTech’s strategic partnership to develop a COVID-19 vaccine, the patent committee was responsible for coordinating all activities in relation to the filing and prosecution of patent rights. Similarly, these committees can serve the purpose of gathering information for parent companies about the development of new IP.

These committees are structured to have members appointed by both partners and are given specific authorities. In some cases, the committee is merely advisory in function, reporting non-binding recommendations related to IP to the Board or steering committee, as was the case in a mobile power JV between Aura Systems and a Chinese counterparty. In other situations, the committee has decision-making authority in particular areas. For instance, in a renewable fuel joint venture, the license agreement states, “Patent Committee to oversee the preparation, filing, prosecution, maintenance and defense of patents and patent applications for which licenses are granted pursuant to this Agreement.” Moreover, a patent committee for a biofuel JV, whose membership must represent each parent company equally, determines the ownership of IP created during the JV’s lifetime, with the decision being binding on the parent companies.

Dealmakers should consider structuring partnerships to have an intellectual property or patent committee in situations in which the JV is charged with actively developing, filing for, maintaining, and/or enforcing IP rights and thus there will be numerous parent decisions related to such items. A committee can streamline these decisions and can include experts who understand the relevant issues.

Dealmakers acknowledge the importance and risks of intellectual property in joint ventures and partnerships – especially when critical to the collaboration’s success or mandate. Given the wide range of IP issues, however, dealmakers may fail to include important terms in their JV Agreements and license agreements. This is certainly the case for IP governance provisions, which generally appear in JV and license agreements less frequently than terms related to IP ownership or licensing. Nevertheless, with careful drafting, dealmakers can be prepared when these issues arise in a partnership and can hopefully avoid governance issues related to IP.